Affectionately known as the Spice Isle, Grenada, a small Caribbean island just under 100 miles north of Venezuela, has long flown under the radar of the tourism and heritage industries. Although the island is widely known for St. George’s Medical School and the 1983 Operation Urgent Fury, it is also home to thousands of years of tangible and intangible cultural heritage that many have either forgotten about or have never learned.

History of Grenada

The story of Grenada begins around 300 CE with the indigenous Amerindians from South America, composed of first the Arawaks and then the Caribs (Encyclopaedia Britannica). Although there is no longer an indigenous population on the island, their footprint can still be found in Grenada, Carriacou, and Petite Martinique. The Amerindians brought their culture and language to the islands that we have found remnants of through ceramics and pottery that tell stories about the tools they used and the diets they had.

One remnant of Amerindian presence can be found on the northern tip of the island In the small coastal village of Waltham, you can find Amerindian Petroglyphs that are referred to as “Carib Stones.” These are believed to date between AD 900-1400 and reflect the Suzan-Troumassoid Occupation (Martin 125). Unfortunately there are still many gaps in what we know about Amerindian presence on the island and more archaeological studies are necessary to fully understand the island’s history pre-colonialism.

Cultural Effects of Colonialism

Following multiple failed attempts at colonization, the French government successfully established a settlement at St. Georges in 1649 (Martin 17). The French ruled until 1762 and it was in those 114 years that most of the Amerindian people were killed. An infamous battle that resulted in the deaths of 40 Caribs occurred in May 1650, where the French ambushed the Caribs in the town of Duquesne; with no escape, the Caribs jumped off a cliff now known as Morne des Sauteurs.

During the French occupation of Grenada, they established plantations and imported African Slaves, opening a new tragic chapter in the island’s history. The island was ceded to Britain in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, but was later recaptured by the French in 1779, and once again restored to Britain in 1783 until Grenada proclaimed independence on February 7, 1974 (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

This period of colonization left a distinct mark on Grenada that can be seen in Georgian architecture, French influence on village and street names, as well as in intangible cultural heritage (syncretism), manifested by the Big Drum Dance and Maroon Fest in Carriacou and Saraca and Shango in Grenada (Martin 237).

Aftermath of Hurricane Ivan

Grenada is home to many historical sites, including historic forts, York House, and the St. George’s Anglican Church. Unfortunately, many of these sites have fallen victim to benign neglect and are not being properly preserved for future generations. The poor state of many sites was only exacerbated by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. York House, best known for being home to the Houses of Parliament, was extremely damaged by the 2004 hurricane. The roof was torn off and windows were destroyed, but little was done to restore and protect this building, so it sits decaying today, nearly 20 years later (Martin 40). This is only one example of many historic or heritage sites on the island that are not getting the attention and preservation they deserve.

Where do we go from here?

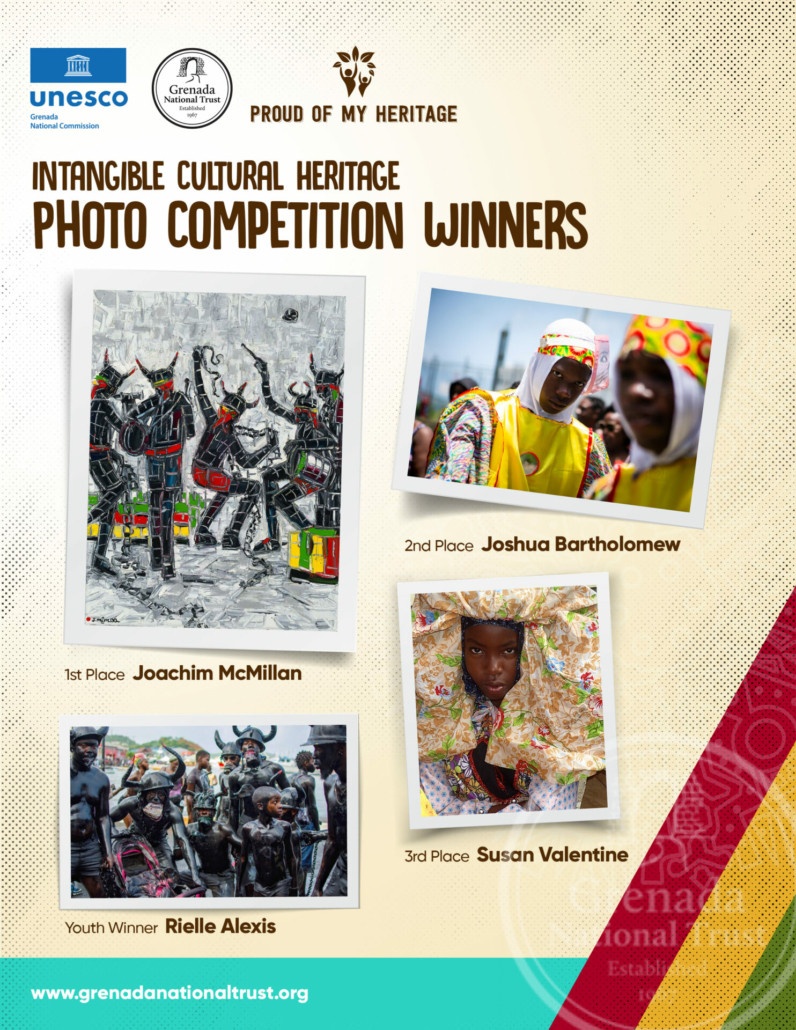

Grenada’s cultural legacy is at a crossroads. The island has a rich culture composed of Soca dancing, Spice Mas or Carnival and cooking with locally grown chocolate and spices. These pieces of intangible cultural heritage or living heritage are what is seen and prioritized by locals and expats alike. It is about time that Grenada begins prioritizing and embracing tangible heritage the same way they do living heritage.

In order for anyone to fully appreciate and learn from Grenada’s heritage, it is imperative that we begin investing in preserving heritage sites. If the proper investments aren’t made as soon as possible, we risk allowing Grenada’s tangible heritage to disappear, along with any chance we have of learning about the history of the island.

The Amerindians who once inhabited this island left behind their stories etched in stone, waiting for us to uncover and understand. The colonial period, with its architectural influence and the birth of unique traditions, shaped Grenada’s identity. Yet, many of these historic sites stand neglected and vulnerable to the ravages of time, as evidenced by the state of York House, the Public Library, the Police Barracks, Fort Matthew, the Government House…to name a few.

By safeguarding Grenada’s heritage, we not only honor its past but also ensure a future where this heritage can continue to educate, inspire, and unite generations to come. We must learn from history, not allow it to fade into obscurity. The time is now. Let’s come together to protect Grenada’s legacy, to preserve its cultural treasures, and to celebrate the diverse tapestry of this extraordinary island. Our actions today will determine whether Grenada’s heritage lives on for future generations or becomes a forgotten chapter in history.

Written by Katharine Rubinetti

Sources

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Grenada summary”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 May. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/summary/Grenada. Accessed 21 November 2023.

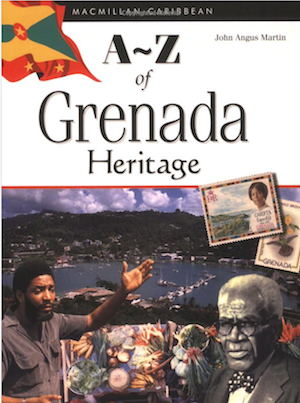

Martin, John Angus. Grenada Heritage. The Grenada National Trust, 2019.